Aspire Health Partners sued Aspire MGT under the Anticybersquatting Consumer Protection Act, 15 U.S.C. §1125(d) (“ACPA”) over defendant’s registration and use of the domain name <aspirehealthgrp.com>. Plaintiff sought a preliminary injunction to stop defendant from using the disputed domain name, but the court denied the request. The court held that plaintiff failed to show that defendant acted with a bad-faith intent to profit from the use of the domain name, a key element of a cybersquatting claim under the ACPA.

To prevail on a cybersquatting claim under the ACPA, a plaintiff must demonstrate that (1) its trademark in the disputed domain name was distinctive when the domain name was registered, (2) the disputed domain name is identical or confusingly similar to that trademark, and (3) the defendant registered the disputed domain name with a bad-faith intent to profit. In this case, the court found plaintiff would not likely succeed on its cybersquatting claim because of deficiencies under the first and third element.

The court found that plaintiff’s mark was not distinctive but instead was descriptive as a “self-laudatory” type of mark. Citing to the well-known McCarthy treatise on trademark law, the court determined that the word “aspire” when applied to healthcare services was of the same sort of use as the word “best” or “super” that extolls some feature or attribute of services and thereby becomes descriptive in nature and likely too weak to be subject to trademark protection.

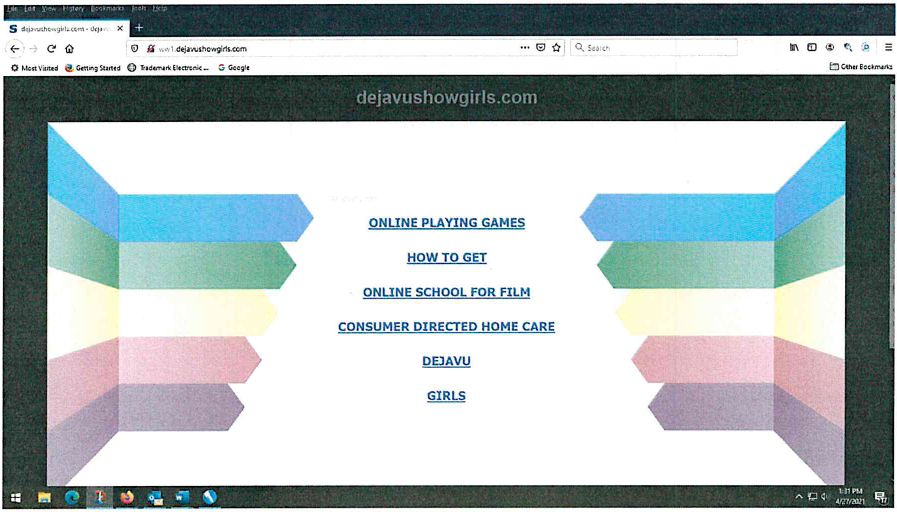

As for the lack of bad faith, the court found that plaintiff had only made a conclusory allegation on the topic. Looking at various factors that courts apply to determine bad faith under the ACPA, the court noted in particular, among other things, that defendant had used the domain name in connection with a bona fide offering of its goods and services, and had not been shown to possess any intent to divert customers form plaintiff’s website or any intent to transfer or sell the domain name for financial gain.

Three Reasons Why This Case Matters:

- Legitimacy in Business Use: Using a domain name for legitimate business purposes can protect defendants against cybersquatting claims.

- Trademark Strength: Descriptive trademarks often face greater challenges in cybersquatting cases without strong evidence of distinctiveness.

- Evidence of Intent: Courts require clear proof of bad-faith intent to profit, not just similarity between domain names, to uphold a cybersquatting claim.

Aspire Health Partners, Inc. v. Aspire MGT LLC, 2024 WL 5169936 (M.D. Fla., Dec. 19, 2024)