Plaintiff set up a Google Drive so that he could collect photos and other content related to a local school board controversy. He thought it was private, but it was actually configured so that anyone using the URL could access the content. After the local controversy escalated, plaintiff’s son emailed some photos to an opponent, and one of those photos contained the Google Drive’s URL. That photo made its way into the hands of defendant, who, using the URL, allegedly reviewed, downloaded, deleted, added, reorganized, renamed, and publicly disclosed contents of the Google Drive.

So plaintiff sued under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, 18 U.S.C. §1030, (the “CFAA”). Defendant moved to dismiss, arguing, among other things, that plaintiff had failed to adequately plead that defendant’s access to the Google Drive was without authorization.

Defendant had argued that her access using the URL could not be considered unauthorized under the CFAA, in accordance with the holding of hiQ Labs, Inc. v. LinkedIn Corp., 31 F.4th 1180 (9th Cir. 2022). In that case, the Ninth Circuit reasoned that “the prohibition on unauthorized access is properly understood to apply only to private information – information delineated as private through use of a permission requirement of some sort.” Thus, for a website to fall under CFAA protections, it must have erected “limitations on access.” And if “anyone with a browser” could access the website, it had no limitations on access.

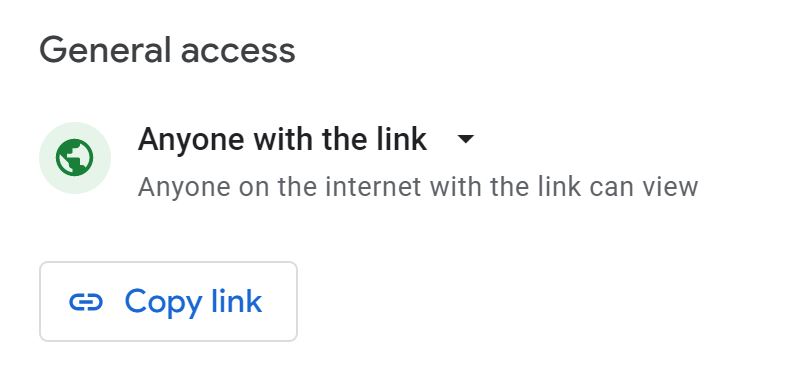

In this case, defendant merely used her web browser and the URL she obtained to access plaintiff’s Google Drive. The portion of the Google Drive was not password protected. And plaintiff had – though inadvertently – enabled the setting that allowed anyone with the URL to access the drive’s contents.

But in the court’s view, the Google Drive nonetheless had limitations that made defendant’s access unauthorized. The court differentiated the situation from one in which just “anyone with a web browser” might access the content, for example, via a web search. One needed to enter a 68-character URL to access the content. And the content was not indexed by any search engines. So the Google Drive was not “per se” public. And defendant’s access – as plaintiff had pled it – was not authorized.

Greenburg v. Wray, 2022 WL 2176499 (D. Ariz., June 16, 2022)

See also: