Plaintiff sued the NBA, accusing it of violating the Video Privacy Protection Act, 18 U.S.C. 2701 (VPPA). Plaintiff claimed that after signing up for the NBA’s online newsletter and watching videos on NBA.com, the NBA shared his viewing history with Meta without his permission. The district court dismissed the case and plaintiff sought review with the Second Circuit. On review, the court vacated and remanded the case for further proceedings.

What is the VPPA?

The VPPA, enacted in 1988, aims to protect consumers’ privacy by restricting video tape service providers from sharing personally identifiable information without consent. The historical circumstances around its enactment, particularly involving Robert Bork, is worth taking a few minutes to read up on.

Key issue – what’s a consumer here?

Plaintiff argued that he qualified as a “consumer” under the VPPA’s definition, which includes any “renter, purchaser, or subscriber of goods or services.” He contended that by providing his email and other personal data in exchange for the NBA’s newsletter, he became a “subscriber,” thus entitling him to privacy protections. According to plaintiff, the NBA’s practice of embedding a “Facebook Pixel” on its website allowed Meta to track users’ video-watching behavior, which constituted a violation of the VPPA’s restrictions.

The NBA, however, argued that plaintiff did not meet the VPPA’s criteria for a “consumer” because the newsletter subscription did not involve any audiovisual services, as required under the law. The NBA further asserted that plaintiff did not suffer a “concrete” injury, a requirement for Article III standing under the standards set out by SCOTUS in TransUnion LLC v. Ramirez. The NBA maintained that merely signing up for a free newsletter did not establish a sufficient relationship to qualify as a “subscriber.”

Lower court proceedings

The United States District Court for the Southern District of New York ruled in favor of the NBA. While it determined that plaintiff had standing to sue, the court dismissed the case on the grounds that plaintiff failed to establish that he was a “consumer” as defined by the VPPA. The court ruled that the VPPA’s scope was limited to audiovisual goods or services, and an online newsletter did not fit this definition. It concluded that merely signing up for a newsletter did not create a relationship that would extend VPPA protections to plaintiff’s video-watching data.

But the appellate court said…

Plaintiff appealed the decision, and the Second Circuit found that plaintiff sufficiently alleged that he was a “subscriber of goods or services” because he provided personal information in exchange for the NBA’s online newsletter. The court emphasized that the VPPA’s language did not strictly limit “goods or services” to audiovisual content, thus broadening the potential scope of who could be considered a “consumer.” This meant that the case would proceed to further legal proceedings to address the other issues in the dispute.

Three reasons why this case matters:

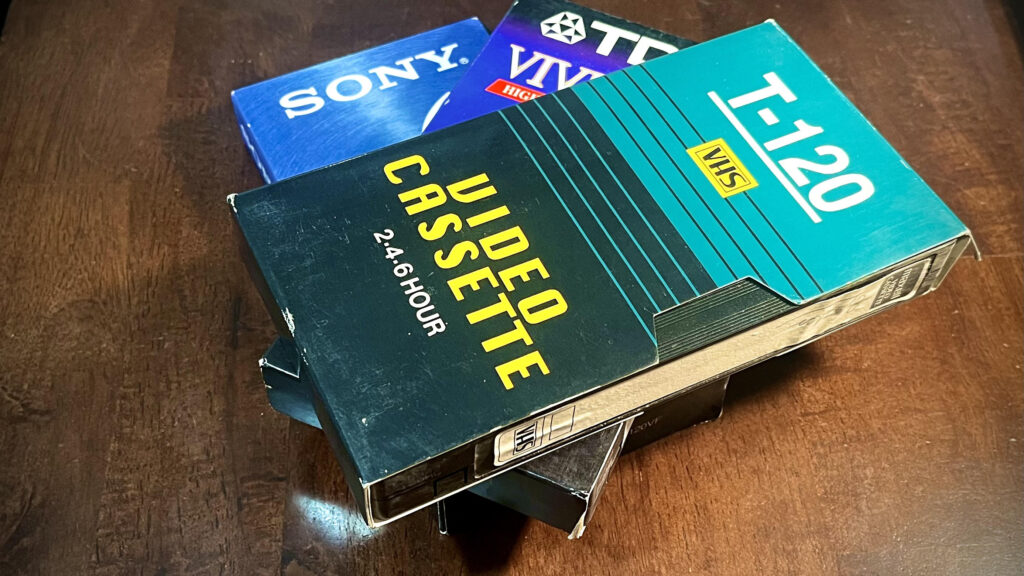

- It clarifies modern VPPA applications: The case explores how the VPPA, with its origins in a VHS-centric era, applies to modern digital interactions, like email newsletters and online video streaming.

- It expands consumer privacy definitions: The court’s interpretation suggests that a “subscriber” could include individuals who exchange personal information for non-monetary services, influencing other privacy claims.

- It influences digital business practices: It affects how businesses should collect and share user data, potentially increasing scrutiny over partnerships involving data tracking and disclosure to third parties such Meta.

Salazar v. NBA, — F.4th —, 2024 WL 4487971 (2nd Cir., October 15, 2024)

See also: Casual website visitor who watched videos was not protected under the Video Privacy Protection Act