A.Z. v. Doe, 2010 WL 816647 (N.J. Super. App. Div. March 8, 2010)

Even if you do just a cursory review of cases that deal with online anonymity, you are bound to come across a 2001 New Jersey case called Dendrite v. Doe. That case sets out a four part analysis a court should undertake when a defamation plaintiff seeks an order to unmask an Internet user who posted the offending content anonymously.

Under Dendrite, a court that is asked by a defamation plaintiff to unmask an anonymous speaker must:

- require the plaintiff to try to notify the unknown Doe speaker that he or she is the subject the unmasking efforts, and give him or her a reasonable opportunity to oppose the application;

- require the plaintiff to identify and set forth the exact statements purportedly made by each anonymous poster that plaintiff alleges constitutes actionable speech;

-

require the plaintiff to produce sufficient evidence supporting each element of its cause of action, on a prima facie basis; and

-

balance the defendant’s First Amendment right of anonymous free speech against the strength of the prima facie case presented and the necessity for the disclosure.

The state appellate court in New Jersey recently had occasion to revisit the Dendrite analysis in a case called A.Z. v. Doe. It found that a defamation plaintiff was not entitled to learn the identity of a person who anonymously sent an email that had content and attached photos that allegedly defamed plaintiff. The court found that plaintiff failed to meet the third factor in the Dendrite analysis, i.e., failed to present a prima facie case of defamation.

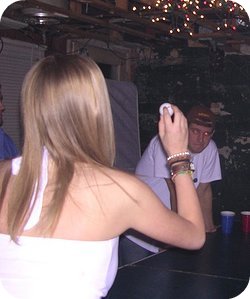

Beer pong is not for honor students

Someone took pictures of plaintiff playing beer pong at a party and posted them on Facebook. That’s all in good fun, except that plaintiff was a minor and belonged to her high school’s “Cool Kids & Heroes” program. Kids get into that program by making good grades and promising to refrain from bad behavior.

A purported “concerned parent” set up a Gmail account (anonymously) and sent an email to the faculty advisor for the Cool Kids & Heroes program. The email had photos attached showing several of the program’s kids doing things they shouldn’t be doing like drinking and smoking pot. In all fairness it should be noted that the picture of plaintiff only showed her playing beer pong — it didn’t actually show her drinking or smoking, though there were cups and beer cans on the table in front of her.

The faculty advisor forwarded the email and images on to school administrators, and the school also notified the police. But law enforcement apparently took no further action.

Plaintiff filed a defamation lawsuit against the anonymous sender of the email and sent a subpoena to Google to find out the IP address from which the message was sent. Google notified plaintiff that it came from an Optimum Online IP address. So plaintiff sent a subpoena to Optimum Online for the identifying information. The ISP notified its customer Doe, and Doe moved to quash the subpoena.

The trial court granted the motion to quash, concluding that plaintiff failed to meet the fourth Dendrite factor (dealing with the First Amendment). Plaintiff sought review with the appellate court, which affirmed but on different grounds.

Why the defamation claim failed

The appellate court agreed that the motion to quash should be granted (that is, that the anonymous sender of the email message should not be identified). But the appellate court’s reasoning differed. It didn’t even need to get to the fourth Dendrite factor, because it held that plaintiff didn’t meet the third factor (didn’t present a prima facie defamation case).

The big problem with plaintiff’s defamation claim came from the requirement that the statement alleged to be defamatory (in this case, that plaintiff had broken the law) needed to be “false.” The court found five reasons why this element had not been met:

- Plaintiff submitted no evidence (like an affidavit) that she wasn’t drinking the night the photo was taken.

- Plaintiff submitted no evidence that law enforcement actually concluded to take no further action. Plaintiff argued their lack of action showed she didn’t break the law.

- Even if there was evidence that law enforcement decided to take no action, that would not have been relevant to the truth of the question of whether plaintiff was drinking. That would only go to show that law enforcement decided not to do anything.

- The photograph attached to the email showing plaintiff playing beer pong would lead one to conclude that she was in “possession” of the alcohol on the table, and that was a violation of the law.

-

Doe submitted other photos from Facebook in connection with the motion to quash which showed plaintiff actually holding a beer.

So the court never got to the question of the First Amendment and how it related to the anonymous email sender’s right to speak. The court concluded that because plaintiff had not put forth a prima facie case of defamation, the anonymous speaker should stay unknown.

Beer pong photo courtesy Flickr user elisfanclub under this Creative Commons license.

Manganese dendrites in limestone photo courtesy Flickr user Arenamontanus under this Creative Commons license.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=c979d9cb-0765-47b2-a007-3e54cc22e6f7)