In 2019, Indiana joined a number of other states and enacted a statute that makes it a crime for a person to distribute an “intimate image” when he or she knows or reasonably should know that an individual depicted in the image does not consent to the distribution. In March 2020, defendant sent a video of himself receiving oral sex to his ex-girlfriend via Snapchat. After being charged under the statute, defendant moved to dismiss, arguing in part that the statute violates both the Indiana and U.S. constitutions. The trial court agreed and dismissed the case. But the state appealed to the Indiana Supreme Court.

What part of the Indiana constitution applied?

The court’s analysis under the Indiana constitution is particularly interesting. Indiana’s constitutional protection in this area reads quite a bit differently than the language of the First Amendment.

Article 1, Section 9 of the Indiana constitution reads as follows:

No law shall be passed, restraining the free interchange of thought and opinion, or restricting the right to speak, write, or print, freely, on any subject whatever: but for the abuse of that right, every person shall be responsible.

The court first had to evaluate whether videos – and in particular the video at issue – were covered by the applicable Indiana constitutional provision. “Our encounters with Article 1, Section 9 have always involved words, thus invoking the ‘right to speak’ clause.” The court held that the video content was protected under the “free interchange” clause of the state’s constitution. “We understand the free interchange clause to encompass the communication of any thought or opinion, on any topic, through ‘every conceivable mode of expression.’” And the court quickly ascertained that being prosecuted for the distribution of the video was a “direct and substantial burden” on defendant’s right to self-expression.

Abuse of rights?

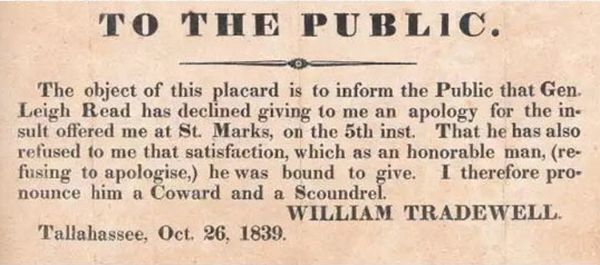

But defendant’s expressive activity in this case – though within his right to free interchange as expressed in the constitution – was an abuse of that right. Looking through the lens of the natural rights philosophy that informed the drafting of the Indiana constitution, the court cited to previous authority (Whittington v. State, 669 N.E.2d 1363 (Ind. 1996)) that explained how “individuals possess ‘inalienable’ freedom to do as they will, but they have collectively delegated to government a quantum of that freedom in order to advance everyone’s ‘peace, safety, and well-being.'” Thus, the court observed that the purpose of state power is “to foster an atmosphere in which individuals can fully enjoy that measure of freedom they have not delegated to government.”

Citing to State v. Gerhardt, 145 Ind. 439 (Ind. 1896), the court evaluated how “[t]he State may exercise its police power to promote the health, safety, comfort, morals, and welfare of the public.” And citing to other authority, the court noted that “courts defer to legislative decisions about when to exercise the police power and typically require only that they be rational.” So the question became whether – approached from the standpoint of rationality – the statute’s restriction on the right to self-expression was appropriate to promote the health, safety, comfort, morals and welfare of the public.

Rationality favored public protection

“Under our rationality inquiry, we have no trouble concluding the impingement created by the statute is vastly outweighed by the public health, welfare, and safety served.” In reaching this conclusion, the court examined, among other things, the tremendous harms of revenge porn – including its connection to domestic violence and psychological injury. Accordingly, the court found the statute did not violate the Indiana constitution.

The court also found that the statute did not violate the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. It held that the statute is content-based and therefore subject to strict scrutiny. Even under this standard, the court found that it served a compelling government interest, and was narrowly tailored to achieve that compelling interest.

State v. Katz, 2022 WL 152487 (Ind., January 18, 2022)

See also: