Deloitte & Touche LLP v. Carlson, 2011 WL 2923865 (N.D. Ill. July 18, 2011)

Defendant had risen to the level of Director of a large consulting and professional services firm. (There is some irony here – this case involves the destruction of electronic data, and defendant had been in charge of the firm’s security and privacy practice.)

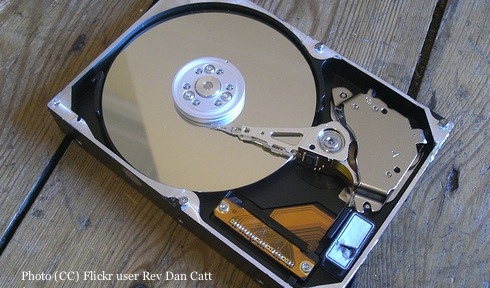

After defendant left the firm to join a competitor, he returned his work-issued laptop with the old hard drive having been replaced by a new blank one. Defendant had destroyed the old hard drive because it had personal data on it such as tax returns and account information.

The firm sued, putting forth a number of claims, including violation of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA). Defendant moved to dismiss for failure to state a claim upon which relief can be granted. The court denied the motion.

Defendant argued that the CFAA claim should fail because plaintiff had not adequately pled that the destruction of the hard drive was done “without authorization.” The court rejected this argument.

The court looked to Int’l Airport Centers LLC v. Citrin, 440 F.3d 418 (7th Cir. 2006) for guidance on the question of whether defendant’s alleged conduct was “without authorization.” Int’l Airport Centers held that an employee acts without authorization as contemplated under the CFAA if he or she breaches a duty of loyalty to the employer prior to the alleged data destruction.

In this case, plaintiff alleged that defendant began soliciting another employee to leave before defendant left, and that defendant allegedly destroyed the data to cover his tracks. On these facts, the court found the “without authorization” element to be adequately pled.