Apple sued defendant NSO, accusing it of, among other things, the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, 18 U.S.C. § 1030 (the “CFAA”), The case dealt with NSO’s creation and distribution of “Pegasus,” a piece of software Apple claimed was capable of covertly extracting information from virtually any mobile device.

Apple alleged NSO fabricated Apple IDs to gain access to Apple’s servers and launch attacks on consumer devices through a method known as “FORCEDENTRY.” This exploit, characterized as a “zero-click” attack, allowed NSO or its clients to infiltrate devices without the device owners’ knowledge or action. The repercussions for Apple were significant, as the company reportedly faced considerable expenses and damages in its efforts to counteract NSO’s activities. These efforts included the development and deployment of security measures and patches, as well as increased legal exposure.

Defendant moved to dismiss the claims. The court denied the motion.

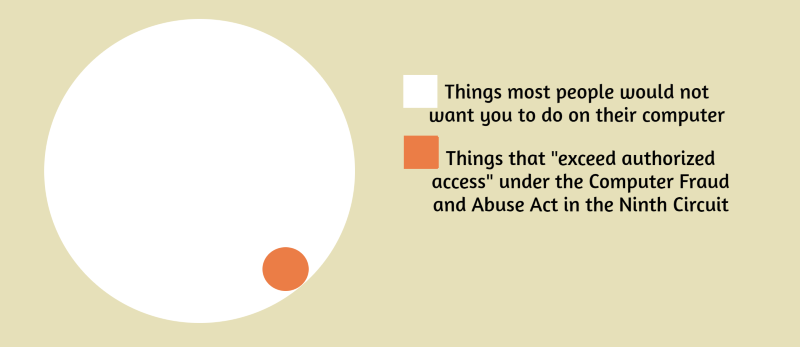

In finding that Apple had properly pled the CFAA claim, the court noted that Apple’s allegations aligned with the anti-hacking intent of the CFAA. Despite NSO’s contention that the devices in question were not owned by Apple and thus not protected under the CFAA, the court observed that Apple’s claims extended to the exploitation of its own servers and services, fitting within the statute’s scope.

Apple Inc. v. NSO Group Technologies Ltd., 2024 WL 251448 (N.D. Cal. January 23, 2024)

Defendant resigned from his job with an IT consulting firm. One of the firm’s customers hired defendant as an employee. Before the customer/new employer terminated the agreement with the IT consulting firm/former employer, defendant used the customer/new employer’s credentials to access and copy some scripts from the system. (Having the new employee and the scripts eliminated the need to have the consulting firm retained.) The firm/former employer sued under the

Defendant resigned from his job with an IT consulting firm. One of the firm’s customers hired defendant as an employee. Before the customer/new employer terminated the agreement with the IT consulting firm/former employer, defendant used the customer/new employer’s credentials to access and copy some scripts from the system. (Having the new employee and the scripts eliminated the need to have the consulting firm retained.) The firm/former employer sued under the