Knowledge that email account had been hacked did not start the statutes of limitation clock ticking for Computer Fraud and Abuse Act and Stored Communications Act claims based on alleged related hacking of Facebook account occurring several months later.

Plaintiff sued her ex-boyfriend in federal court for allegedly accessing her Facebook and Aol email accounts. She brought claims under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, 18 U.S.C. § 1030 (“CFAA”), and the Stored Communications Act, 18 U.S.C. § 2701, et seq. (“SCA”).

Both the CFAA and the SCA have two-year statutes of limitation. Defendant moved to dismiss, arguing that the limitation periods had expired.

The district court granted the motion to dismiss, but plaintiff sought review with the Second Circuit Court of Appeals. On appeal, the court affirmed the dismissal as to the email account, but reversed and remanded as to the Facebook account.

In August 2011, plaintiff discovered that someone had altered her Aol email account password. Later that month someone used her email account to send lewd and derogatory sexually-themed messages about her to people in her contact list. A few months later, similar things happened with her Facebook account — she discovered she could not log in in February 2012, and in March 2012 someone publicly posted sexually-themed messages using her account. She figured out it was her (now married) ex-boyfriend and filed suit.

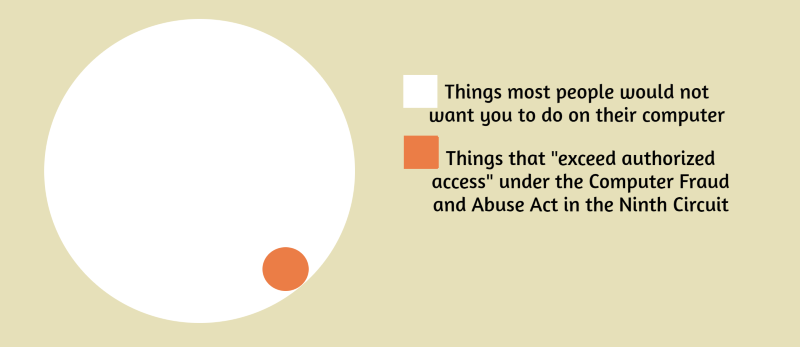

The district court dismissed the claims because it found plaintiff first discovered facts giving rise to the claims in August 2011, but did not file suit until more than two years later, in January 2014. The Court of Appeals agreed with the district court as to the email account. She had enough facts in 2011 to know her Aol account had been compromised, and waited too long to file suit over that. But that was not the case with the Facebook account. The district court had concluded plaintiff knew in 2011 that her “computer” had been compromised. The Court of Appeals observed that the lower court failed to properly recognize the nuance concerning which computer systems were being accessed without authorization. Unauthorized access to the Facebook server gave rise to the claims relating to the Facebook account. The 2011 knowledge about her email being hacked did not bear on whether she knew her Facebook account would be compromised. The court observed:

We take judicial notice of the fact that it is not uncommon for one person to hold several or many Internet accounts, possibly with several or many different usernames and passwords, less than all of which may be compromised at any one time. At least on the facts as alleged by the plaintiff, it does not follow from the fact that the plaintiff discovered that one such account — AOL e-mail — had been compromised that she thereby had a reasonable opportunity to discover, or should be expected to have discovered, that another of her accounts — Facebook — might similarly have become compromised.

The decision gives us an opportunity to think about how users’ interests in having their data kept secure from third party access attaches to devices and systems that may be quite remote from where the user is located. The typical victim of a hack or data breach these days is not going to be the owner of the server that is compromised. Instead, the incident will typically involve the compromising of a system somewhere else that is hosting the user’s information or communications. This decision from the Second Circuit recognizes that reality, and contributes to the reasonable opportunity for redress in those situations.

Sewell v. Bernardin, — F.3d —, 2015 WL 4619519 (2nd Cir. August 4, 2015)

Evan Brown is an attorney in Chicago helping clients manage issues involving technology and new media.

Evan Brown is a technology and intellectual property attorney in Chicago. This content originally appeared on

Evan Brown is a technology and intellectual property attorney in Chicago. This content originally appeared on

Plaintiff sued defendant (a former employee) under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (“CFAA”) alleging that defendant intentionally and without authorization accessed plaintiff’s computers, intranet, and email system and sent plaintiff’s confidential customer information to his personal email account. Defendant allegedly used this information when he went to work for a competitor. Plaintiff also alleged that defendant attempted to conceal his actions by deleting the outgoing messages from the work email account.

Plaintiff sued defendant (a former employee) under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (“CFAA”) alleging that defendant intentionally and without authorization accessed plaintiff’s computers, intranet, and email system and sent plaintiff’s confidential customer information to his personal email account. Defendant allegedly used this information when he went to work for a competitor. Plaintiff also alleged that defendant attempted to conceal his actions by deleting the outgoing messages from the work email account.  Defendant resigned from his job with an IT consulting firm. One of the firm’s customers hired defendant as an employee. Before the customer/new employer terminated the agreement with the IT consulting firm/former employer, defendant used the customer/new employer’s credentials to access and copy some scripts from the system. (Having the new employee and the scripts eliminated the need to have the consulting firm retained.) The firm/former employer sued under the

Defendant resigned from his job with an IT consulting firm. One of the firm’s customers hired defendant as an employee. Before the customer/new employer terminated the agreement with the IT consulting firm/former employer, defendant used the customer/new employer’s credentials to access and copy some scripts from the system. (Having the new employee and the scripts eliminated the need to have the consulting firm retained.) The firm/former employer sued under the