Today the Ninth Circuit issued an opinion in the case of Vernor v. Autodesk [PDF], making an important ruling about copyright, software and the first sale doctrine. At a fundamental level, however, one could wonder whether the case is all that big a deal, since the first sale doctrine concerns rights that the owner of a physical copy of a work has. For software — especially these days when an increasing amount of software is either distributed over the internet or provided in the cloud — questions about the rights associated with physical copies are becoming increasingly irrelevant.

No doubt the distribution of physical copies of software is less important than it was in the past. But the Vernor case is worth looking at inasmuch as the ruling could translate into some potentially wacky arrangements depending on the desires of copyright owners and the accompanying restrictions they may put on the uses of their works. The holding of the case is not limited to software, but to any copyrighted work capable of being distributed in physical form. As Vernor’s attorney Greg Beck has written, “there is no obvious reason why other publishing industries couldn’t begin imposing the same terms. If they do, it may be the end of ownership of books and music.” (I’m proud to mention that Beck has been a guest blogger here at Internet Cases.)

What the case was about

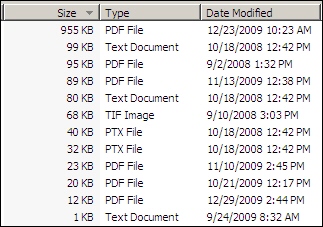

Vernor bought several used copies of AutoCAD software from a customer of Autodesk, which is the software’s original distributor and copyright owner. Vernor then tried to sell those copies on eBay. Autodesk asserted that this sale of the copies violated Autodesk’s exclusive rights under the Copyright Act to distribute the software. So Vernor filed suit to ask the court to declare that such sales were not infringing. (Cases like these, where the accused goes on a preemptive offensive, are called declaratory judgment actions.)

The trial court found in Vernor’s favor. Autodesk sought review with the Ninth Circuit. On appeal, the court reversed, holding that Vernor could not rightly assert that his conduct was protected under copyright law’s first sale doctrine, and that Vernor’s customers’ installation of the software was not protected by the essential step defense.

These defenses failed because the court found that Vernor (and his customers) were merely licensees of the software, not owners.

The Software License Agreement

When Autodesk sold the software to CTA (the company from whom Vernor bought the discs before trying to sell them on eBay), it included a shrinkwrap license agreement, as well as a screen containing the same terms that appeared during the installation agreement.

The agreement provided, among other things, that the software was being provided under a limited license and that Autodesk retained ownership of the copyright in the software. It also placed onerous restrictions on the use and transfer of the software, e.g., the user could not rent, lease or transfer it to other users, or transfer it out of the Western Hemisphere, either physically or electronically.

The first sale doctrine

In general, the owner of a copyright in a work has the exclusive right to determine how copies of the work are distributed. The century-old first sale doctrine, however, is an exception to this general rule.

Under Section 109 of the Copyright Act (17 USC 109), the “owner of a particular copy” of a work may sell or dispose of his or her copy without the copyright owner’s authorization. Selling the copy of a painting you by at an art auction, for example, should not subject you to copyright infringement.

The essential step defense

The Copyright Act also provides that the owner of the copyright in a work has the exclusive right to make copies of the work. But there’s an exception to that exclusivity when it comes to software — the RAM copy made when the software is being used, according to Section 117 of the Copyright Act, cannot give rise to an infringement if that copying is being done by the “owner of a copy” of the software as an “essential step” in using the program.

The lower court’s decision

Vernor won at the lower court level because the court held that he was the “owner” of the copies of software he had bought, and therefore was protected by the first sale doctrine. His customers, also as owners, would be protected by the essential step defense.

Why these defenses failed

The court of appeals held otherwise, namely, that Vernor (as well as the company from whom he had bought the copies, and his customers) were merely licensees and not owners of the software. Only “owners” can claim protection under the first sale doctrine and the essential step defense.

The court looked to the circumstances surrounding the transfer of the software, and formulated the following test to determine that a software user is merely a licensee when the copyright owner: (1) specifies that the user is granted a license, (2) significantly restricts the user’s ability to transfer the software, and (3) imposes notable use restrictions.

In this case, all these criteria were met. Since neither Vernor nor the company he bought the software from were “owners,” these defenses were not available.

Room for criticism

The decision is subject to criticism in a number of ways. First, it might go against the sensibilities of many ordinary folks who think, quite naturally, that when you buy something (like a CD containing software), you own it. This case confirms that that is not always the case.

A second possible criticism is how the case makes possible some strange situations not involving software. What’s to stop hard copy book publishers from entering into shrinkwrap agreements with people who buy the books, purporting to retain ownership and calling the arrangement a license, while placing restrictions on use and transfer? Under the test in this case, it could be an infringement to lend or sell or otherwise distribute that book. Seems like a dangerous way to lock up information. But I guess it’s better than including curses as DRM.

Finally, the case lends itself to criticism in the way it gives great power to the software companies to really tie up tangible media to the detriment of consumers. Once an application has been sold once, where’s the harm to the software company if it’s transferred to someone else? The company has already been paid once, why must it insist on getting paid again? This grabbiness is really no surprise, though, especially when one sees that the likes of the Business Software Alliance joined as amici on the side of Autodesk.

In any event, tangible media for software is becoming a thing of the past. To the extent this case allows some negative consequences, the move to the cloud will mitigate that negativity.