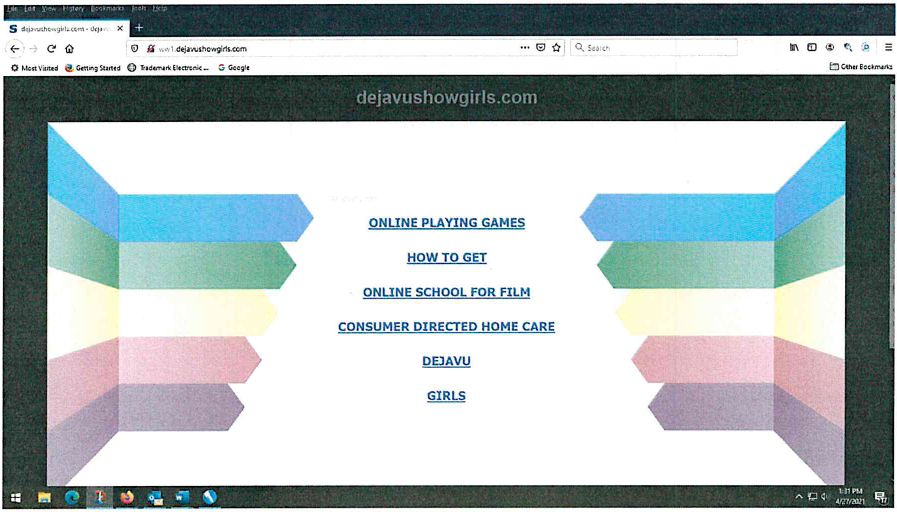

NameFind is a GoDaddy company that holds registrations of domain names and seeks to make money off of them by placing pay-per-click ads on parked pages found at the domain names. Global Licensing owns the DEJA VU trademark that is used in connection with strip clubs and other adult-related services. When NameFind used the domain name dejavushowgirls.com to set up a page of pay-per-click ads, Global Licensing sued, raising claims under the federal Anticybersquatting Consumer Protection Act (ACPA), 15 U.S.C. 1125(d).

Arguing that the cybersquatting claim had been insufficiently pled, NameFind moved to dismiss. The court denied the motion.

To establish a “cybersquatting” claim under the ACPA, a plaintiff must establish that: (1) it has a valid trademark entitled to protection; (2) its mark is distinctive or famous; (3) the defendant’s domain name is identical or confusingly similar to, or in the case of famous marks, dilutive of, plaintiff’s mark; and (4) defendant used, registered, or trafficked in the domain name (5) with a bad faith intent to profit. DaimlerChrysler v. The Net Inc., 388 F.3d 201 (6th Cir. 2004) (citing Ford Motor Co. v. Catalanotte, 342 F.3d 543, 546 (6th Cir. 2003)).

Identical or confusingly similar

NameFind first argued that the court should dismiss the ACPA claim because there were no “non-conclusory” allegations explaining how the content on its website could be confusingly similar to plaintiff’s entertainment services. The court found this argument unpersuasive, however, because the content of the website was not important in evaluating this element. Instead, the court was to make a direct comparison between the protected mark and the domain name itself, rather than an assessment of the context in which each is used or the content of the offending website. It found the disputed domain name and plaintiff’s mark to be identical or confusingly similar because the disputed domain name incorporated plaintiff’s mark, and there were no words or letters added to plaintiff’s mark that clearly distinguished it from plaintiff’s usage.

Bad faith intent to profit

The court likewise rejected NameFind’s second argument, which was that plaintiff had not sufficiently pled NameFind’s bad faith intent to profit. The main point of the argument was that most of plaintiff’s allegations were made “on information and belief”. (That phrase is used in lawsuits when the plaintiff does not know for sure whether a fact is true, so it hedges a bit.) The court observed that allegations made on information and belief are not per se insufficient.

In this case, the court stated that the “on information and belief” allegations should not be considered in isolation, but should be considered in the context of the entire Complaint, including the factual allegations that: (1) NameFind had no intellectual property rights in or to the DEJA VU mark; (2) the disputed domain name was essentially identical to plaintiff’s mark and did not contain defendant’s legal name; (3) plaintiff did not authorize or consent to such use; (4) the domain name was configured to display pay-per-click advertisements to visitors, which provided links to adult-related entertainment sites; (5) as such, the disputed domain name was likely to be confused with plaintiff’s legitimate online location and other domain names, and deceive the public; and, (6) defendant’s website harmed plaintiff’s reputation and the goodwill associated with its marks by causing customers to associate plaintiff with the negative qualities of defendant’s website.

Global Licensing, Inc. v. NameFind LLC, 2022 WL 274104 (E.D. Michigan, January 28, 2022)