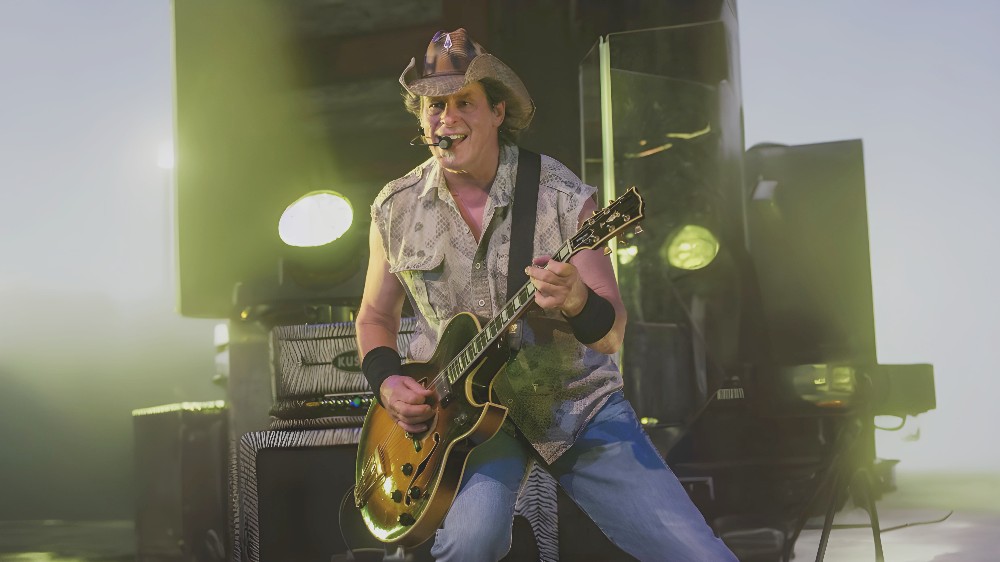

Plaintiff photographer sued defendant news website for copyright infringement over a photo of Ted Nugent that defendant used in an online article. The lower court granted summary judgment for defendant, finding that its use of the photo was fair use. Plaintiff sought review with the Fourth Circuit. On review, the court reversed, applying the factors set out in 17 U.S.C. § 107 in finding the use of the photo was not fair use.

For the first fair use factor, the court found that defendant’s use of the photo was not transformative and was commercial. This caused the factor to weigh against fair use. It looked to the recent Supreme Court case of Andy Warhol Found. for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 598 U.S. 508 (2023). The court noted that in a manner similar to what happened in the Warhol case, plaintiff took the photo of Ted Nugent to capture a “portrait” of him, and defendant used the photo to “depict” the musician. Accordingly, the two uses “shared substantially the same purpose.” The court actually found that defendant in this case had “less of a case” for transformative use than the Andy Warhol Foundation did, because unlike in Warhol, defendant did not alter or add new expression beyond cropping negative space. And though the article in which the photo appeared did not generate much revenue for defendant, the relevant question to determine commercial use was whether defendant stood to profit, not whether it actually did profit.

Though the district court did not address the second and third fair use factors, the appellate court looked at those factors, and found they did not support fair use. Looking at the nature of plaintiff’s photo, the court observed that plaintiff made several creative choices in capturing the photo, including angle of photography, exposure, composition, framing, location, and exact moment of creation. As for the third factor, the court found it to weigh against fair use because defendant copied a significant percentage of the photo, only cropping out negative space while keeping the photo’s expressive features.

Finally, the court also found that the fourth fair use factor weighed against fair use. The court concluded that if defendant’s unauthorized use became “uninterrupted and widespread,” it would adversely affect the potential market for the photo. It emphasized the notion of the potential market. In this case, there was at least one instance where plaintiff had allowed use of his photo for free, and he also made it available for free subject to a Creative Commons license, requiring attribution in return. But that did not change the outcome, given that he customarily licensed if for either money or attribution.

Philpot v. Independent Journal Review, — F.4th —, 2024 WL 442066 (4th Cir., February 6, 2024)

See also:

- Willie Nelson meme on Facebook was not clearly fair use

- YouTubers get fair use win in copyright suit brought over reaction video

- Ooh la Fair Use

Ted Nugent photo by Republic Country Club, under this Creative Commons license. Changes made: frame expanded, image color modified and background enhanced using generative AI.